Blue whales are the largest animals on Earth, and their booming vocalizations travel hundreds of kilometers underwater. A pattern in their vocalizations, recently discovered, may help to protect these endangered giants.

Researchers from MBARI, Stanford University, and other institutions worked together to reveal a link between blue whale songs and essential behaviors like foraging and migration. There’s a pattern to the trills and bellows of blue whales. Like human songs, whale songs consist of rhythmic, repeated sequences of sounds that have different pitches. Although both male and female blue whales vocalize, only the males sing. By listening carefully to their songs, researchers can hear when the blue whale population off Central California is focused on feeding or migrating.

Each year, blue whales embark on a 6,400-kilometer (4,000-mile) journey between feeding grounds in North America’s fertile, temperate seas and breeding grounds in the warm, tropical waters of Mexico and Central America. Scientists have learned when male blue whales are feeding, they sing more at night, but once their migration gets underway, they start to sing more during the day.

MBARI technology opened a window into this dimension of blue whales’ lives.

Nine hundred meters (nearly 3,000 feet) below Monterey Bay’s surface sits the Monterey Accelerated Research System cabled observatory, or MARS. For more than a decade, MBARI scientists and engineers have used this platform to develop and test various tools and technologies that have provided valuable insight into the ocean and its inhabitants. A 52-kilometer (32-mile) cable provides power to the instruments deployed at the observatory and gives MBARI researchers a real-time uplink to monitor their equipment and experiments. Some tools are installed at the observatory temporarily, while others are deployed long term to support MBARI’s strategic goal of maintaining a persistent presence in the deep sea. These tools gather physical, biological, geological, and chemical data from the observatory and its surroundings.

A digital broadband hydrophone installed on the MARS observatory has helped MBARI researchers and collaborators across Monterey Bay learn more about the soundscape beneath the surface. Since 2015, this underwater microphone has been recording sounds from the depths of Monterey Bay.

The ocean’s soundscape changes constantly. Sounds from living organisms, natural processes, and human activities all coalesce into a dynamic underwater symphony—the clicks of dolphins hunting for food, the pitter-patter of raindrops falling on the surface during a storm, the boom of shipping traffic. Computational analysis of the audio captured by the hydrophone can tease out individual sounds.

Signal processing and machine learning—from automated recognition of the vocalizations of marine mammals to long-term statistical description of sounds—are used to sift through the cacophony and gather a library of data for researchers not just at MBARI, but at the Naval Postgraduate School, Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, the University of California at Santa Cruz, and the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Together, we’re listening and learning from this trove of acoustic data.

After analyzing five years of hydrophone recordings and focusing on sound frequencies most used by blue whales, MBARI and Stanford researchers noticed distinct seasonal changes in blue whale vocalizations.

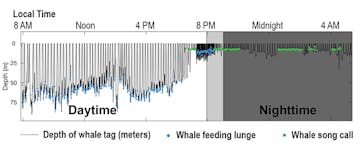

Data from a tagged blue whale, Balaenoptera musculus, shows how the whale made feeding dives during the day but stayed near the surface and sang at night. Image courtesy of William Oestreich.

During summer and early fall, the blue whale population heard at MARS sings much more during the night than during the day. Later in the fall and into winter, the whales begin singing more during the day—a change that coincides with the time of year when the whales reduce feeding and begin their annual southward migration. (And between February and June, the song signal quiets altogether as the whales move to waters well out of earshot of our hydrophone.)

Researchers had previously observed differences in vocalizations between day and night, but this was the first time they saw a seasonal change in the day/night pattern repeated year after year.

The key to understanding this seasonal bioacoustic pattern within the whale population was to observe the world from the backs of individuals. In a lab, we cannot study an animal that spans 33 meters (110 feet) and weighs 181 metric tons (200 tons), so researchers bring the lab to the whale. Stanford researchers have developed and deployed groundbreaking tagging technologies to unravel the natural history of magnificent whales in their own environment. Researchers outfitted foraging blue whales with tags carrying sensors that recorded not only vocal, foraging, and migratory behavior but also environmental data and video. Some tags carried accelerometers that recorded the animal’s motions and, by extrapolating vibrations within the animal’s body, its songs, while other tags carried miniature hydrophones.

In the summer, the accelerometers on these tags reported whales spent much of their day feasting. The tags recorded dives up and down in the water column—typically about 10 minutes underwater and three minutes above—a telltale sign the whales were lunge feeding on tiny shrimp-like krill and bulking up ahead of their long journey south. During the day, the whales produced about three calls per hour. At night, the tags logged shallow dives, and the whales were much more vocal, producing seven to 11 calls per hour. These patterns recorded in individual whales echoed population-level trends observed by MBARI’s hydrophone.

Stanford’s tags also captured the whales’ transition between foraging and migrating behaviors. In their feeding grounds off Central California, the whales sang during the evening and stayed relatively quiet during the day. But this pattern inverted simultaneously when the tags recorded the start of the whales’ southward migration. Once again, this matched the data heard by MBARI’s hydrophone eavesdropping on the Northeastern Pacific population as a whole.

The ability to acoustically detect population-level transitions in behavior provides a revolutionary tool for the comprehensive study of the life history of a dispersed population of whales. Critically, this research also has implications for safeguarding populations of an endangered marine mammal.

Real-time detection of behavioral signals in blue whales can inform dynamic management efforts to mitigate anthropogenic threats to this population. We now know the acoustic signature of migration, so we can keep an ear out for the shifting schedule of vocalizations and hear, in real time, when blue whales leave their lush feeding grounds and begin their journey to the tropics. Knowing when and where this migration gets underway, we can advise ships to steer clear of the whales’ route or tell ship captains to take precautions to reduce the risk of fatal collisions that threaten these gentle giants.

Since its inception, MBARI has aimed to bring science and engineering together to find innovative strategies and solutions for studying the largest environment on Earth. This collaborative research leveraging MBARI technology to reveal animal behavior exemplifies the vision of MBARI founder David Packard.

This video shows a spectrogram of the blue whale “A,” “B,” and “C” calls, paired with audio of these same calls played back at 10 times their original speed to make them easier to hear. The audio was recorded from MBARI’s deep-sea hydrophone on the seafloor just outside of Monterey Bay. New research shows that the day/night pattern of “B calls” can be used to indicate whether the whales are feeding or migrating.