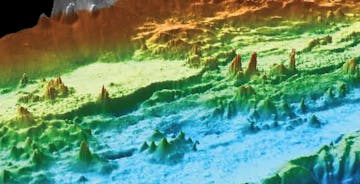

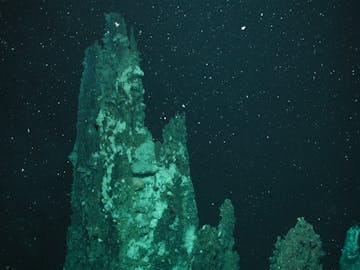

Prior to the high-resolution mapping surveys, American and Canadian scientists had named about 47 active hydrothermal vents, most of which lie within five major vent fields. They also discovered that this region not only had vast numbers of chimneys but also had some of the tallest hydrothermal chimneys known on any mid-ocean ridge in the world. The tallest of these chimneys, which they named “Godzilla,” reached a height of 45 meters (150 feet) before it toppled over in 1995.

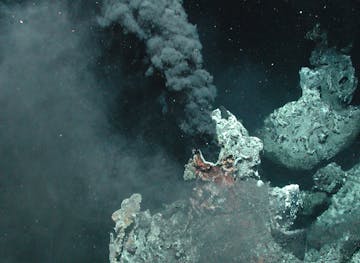

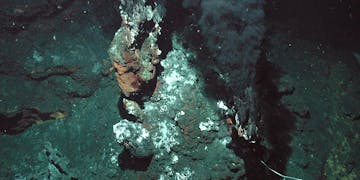

Active chimneys typically form where superheated water (over 300 degrees Celsius; 570 degrees Fahrenheit) flows up through cracks in the seafloor. If this flow is strong and lasts long enough, the chimney may grow taller and taller until it becomes unstable and topples over. However, many seafloor cracks and chimneys become clogged by mineral deposits. At this point, the chimney becomes inactive and stops growing but may remain standing for hundreds of years. Meanwhile, the fluids from the clogged chimney find their way upward through different cracks in the seafloor to form new chimneys nearby.

To figure out what makes the Endeavour Segment unique, the researchers compared the types of chimneys at Endeavour with those found at the Alarcón Rise (near the southern tip of Baja California in Mexico), another spreading center that MBARI has mapped in detail. They found that the Endeavour Segment had many more chimneys, but a lower proportion of active chimneys.