With an abundance of life from the largest whales down to the tiniest zooplankton, Monterey Bay illuminates the wonders of the open ocean, midnight zone, and the deep seafloor—all within a few kilometers of MBARI’s facilities. But a new analysis suggests that this vibrant ecosystem also reflects how climate change impacts biological communities on a much larger scale.

Researchers at MBARI first installed oceanographic instruments on two moorings (M1 and M2) in Monterey Bay in 1989, and since then, M1 has provided a near-continuous stream of data. Simultaneously, monthly time-series cruises began sampling at sites C1, M1, and M2. Some of the samplings included the collection of material on filters that were frozen in liquid nitrogen for later analysis.

The filters—originally intended for measuring photosynthetic pigments—also captured the sloughed-off cells, waste, and free DNA from organisms passing through the water. This DNA has become known as environmental DNA (eDNA). Using new techniques to analyze the eDNA in a decade of archived samples from the C1 site, the team recently unlocked a treasure trove of biological data.

They found that Monterey Bay experienced dramatic shifts in community composition, from microbes to fish, closely related to various climate indices tracked through the Monterey Bay time series. Moreover, analysis from that single location reflected trends seen throughout the California Current. The results are promising not only as a step toward using eDNA as a broad tool for biological analysis, but also for the importance of Monterey Bay as a window into larger trends along the coast.

Now the team is looking to analyze the monthly samples taken at the M1 and M2 sites over the same period in hopes of further linking biological to physical changes. The R/V Western Flyer is scheduled for a cruise in April to collect samples for eDNA analysis at these sites, and further offshore, to understand how community composition shifts over spatial scales.

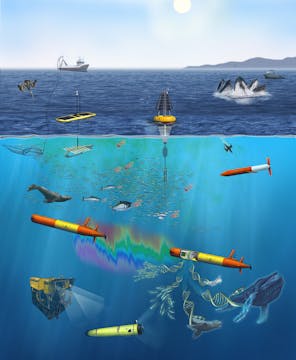

Some of the technologies used during the CANON experiment include MBARI's long-range autonomous underwater vehicles (LRAUVs) and environmental DNA. Illustration: Kelly Lance © MBARI

The Biological Oceanography Group also regularly collects eDNA samples during MBARI’s semiannual Controlled, Agile, and Novel Ocean Network (CANON) experiments, from ships and autonomous vehicles, which allow the team to analyze the results in conjunction with ROV dives, time-lapse video, and acoustic measurements for comparison and context.

MBARI research was recently featured in NOAA’s Science and Technology strategic planning focus areas on uncrewed systems and ‘omics—the suite of advanced methods used to analyze material such as DNA, RNA, proteins, or metabolites. Several MBARI teams will be collaborating with NOAA to increase capacity and processing power for both autonomous sampling and eDNA analysis.

One challenge still ahead for researchers is developing technology that would enable autonomous technology like long-range autonomous underwater vehicles (LRAUVs) equipped with Environmental Sample Processors (ESPs) to send back data instead of physical samples.

This advance would enable biologists to retrieve biodiversity information globally, in near real time, in a manner akin to physical and chemical oceanographers retrieving measurements of temperature, salinity, nitrate, and pH. Ultimately, the ability to collect biological data autonomously and routinely would make it possible to holistically study how and why communities in Monterey Bay and the ocean at large are changing over time.